10 Methods for In-Depth Code Review

November 23, 2021

For many of us, code review is like eating broccoli: We know it's good for us, but we hate it. Here are my 10 tangible tips to improve the value of code reviews, and hopefully make them less distasteful.For many of us, code review is like eating broccoli: We know it’s good for us, but we hate it.

This leads many to do superficial code reviews, which are much less effective than they should be.

Is there anything we can do to encourage more in-depth code reviews that lead to learning, and better code? I believe there is.

In this article, I’ll go through a number of tips for both the reviewer and reviewee to improve the value you get from code reviews, and maybe even make the process a little less distasteful.

All of these suggestions (except the first one) assume that your code is reviewed as part of a pull-request workflow such as GitHub flow or trunk-based development with PRs. There are other methods of code review, but they’re much less prevelant, so I’m not addressing them today.

1. Ensemble Programming

Let’s start by getting the obvious answer out of the way.

Ensemble programming is the practice of two or more developers sitting at a single keyboard (possibly virtually via screen sharing), and verbally working together on a single piece of code. The person controlling the keyboard, known as the driver, may swap roles with the observer or navigator, possibly at regular intervals, or on an ad-hoc basis. The point is that all code is seen in real time by two developers. The unique roles of driver and navigator also engage different parts of the brain, which allow the pair to be more effective than a single developer working alone, as the proponents point out.

By doing this, all code is reviewed in “perfect” depth as soon as it is written.

Many teams feel this obviates the need for a later asynchronous code review, although opinions differ.

Of course pair programming isn’t always possible for all teams, or at all times. If your would-be pairing partners work in a different time zone or simply have different schedules, if company politics prohibit this practice, if you’re just not comfortable with it, or if you believe that even after pair programming, another review pass is valuable, keep reading.

2. Create small pull requests

Submit a 10-line pull request and review will take 10 minutes and find six problems.

Submit a 1,000-line pull request and review will take 10 minuntes and find zero problems.

It may seem a bit counter-intuitive, but the best way I know to get in-depth code review is to make your PRs smaller.

It’s a well established fact that humans like small, digestiable bits of data. Even when the absolute amount of data is the same, splitting large data sets into smaller ones helps us consume them more effectively. This is why newspaper columns are narrow, and why articles are broken up with illustrations and subheadings.

It then follows logically, as well as empircally, that a 10 100-line PRs will get better review than a single 1000-line PR, even if they contain the exact same changes in aggregate.

Reviewees, keep your PRs small, and easy to review. Reviewers, when you see a large PR, ask the author to split it into several smaller PRs.

3. Work in small batches

This is closely related to creating small pull requests. Lest you be tempted to write your 1,000-line patch, then split it into 10 smaller PRs before review, consider the benefits of working in smaller batches:

- More frequent PRs means more frequent feedback

- Small, focused PRs are easier to think about as an author

- Small PRs tend to be reviewed sooner

- Small PRs have fewer merge conflicts

And perhaps one of the most counter-intuitive reasons to use smaller PRs:

- When everyone on the team is accustomed to working in smaller batches, it’s easier to review others’ work without harmful interruptions

4. Prioritize code review over writing code

When it takes hours or days to get code reviewed, we tend to batch more code into each review. This leads to larger pull requests. Larger pull requests take longer to review, so reviewers tend to put them off. This in turn means it takes hours or days to get code reviewed…

To break out of this negative feedback loop, we need to attack every step in the process. Smaller, more frequent pull requests, as already discussed, is only part of it. The other key piece is frequent code review.

One simple rule can break your team out of this habit: Always review code before writing code.

When you sit down to start the day, before opening your IDE, see if there is any code awaiting review.

When you createa a PR, before starting your next task, see if there are is any code awaiting review.

Attack code reviews like a tribbles, which will multiply and spread if they aren’t exterminated immediately.

When this and the previous 2 suggestions are used together, you’ll quickly find that your entire team is operating at a fast caedance of write-review-merge, that takes an hour or less. The logical next step might be peer programming, to reduce the cycle time even further!

5. Enforce styling with a tool

Stop reviewing coding style. Seriously. Stop it. It’s a big fat waste of everyone’s time and energy. And it’s often fraught with unnecessary emotions.

Use a code formatting tool. Add it to your pre-merge automation. If any code in the PR doesn’t conform to standard, it should automatically fail the PR. Which style you use is much less important than the fact that your style is automatically enforced.

I don’t know about you, but I certainly prefer a tool telling me I should use tabs instead of spaces, rather than a colleague telling me. Maybe I get angry with the tool, but at least I don’t have to sit across from that tool at lunch later. Save that time and energy for reviewing the code’s functionality and structure.

6. Use linters

Most languages come with a large collection of linters. Use them. Use many of them. Not only can linters improve code quality, security, and complexity, they offload a certain amount of cognitive load from the code reviewer.

7. Write readable code

Code readability is subjective. But it’s also incredibly important.

Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand.

— Martin Fowler

As a code author, write your code with your (human) audience in mind.

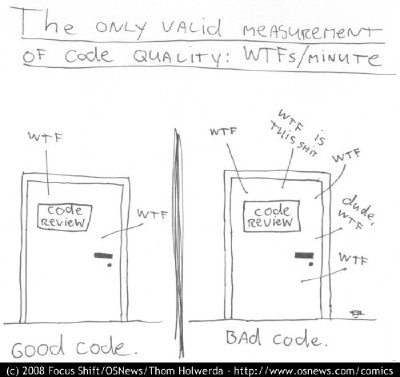

As a code reviewer, anytime you catch yourself thinking “WTF?” during a code review, leave a comment for improvement. Even if you figure it out on your own, it’s a great opportunity for the author to learn to write more readable code.

This is one reason that juniors should be actively involved in reviewing seniors’ code.

8. Do only one thing

Every commit, every pull request should do one thing and only one thing. Did you find a bug while adding a feature? Commit the bug fix in a separate PR.

Do you need to re-format an entire file to conform to new formatting rules? Make that a separate PR.

There’s nothing harder than trying to review a bug fix, new feature, and performance improvement all muddled together in a single PR.

Commit early. Commit often. Commits, and PRs, are free.

9. Write descriptive commit and PR messages

Code review isn’t just about code. Commit and PR messages are also a meaningful part of the pull request. When you’re trying to debug something done by somebody 9 months ago, who’s no longer with the company, there’s nothing more frustrating than a commit message that just says “fix” for a 300-line change.

10. Be polite

Never use a code review as an excuse to showcase your superior technical ability. Be polite. Offer friendly suggestions for improvement. Be humble. Be honest when your suggestion is only an opinion, and not a deal-breaker for you.

Nobody likes a rude reviewer, and will seek out ways to avoid them. This means that the best way to get code authors to be open, to create small, easily-reviewed PRs, and to generally buy into the system is to make code reviews as enjoyable as possible. This means making them polite, and making them an opportunity for bi-directional learning.