Why NPS isn't very useful: A look at the NPS of SAFe

February 12, 2022

Often criticized for its statistical silliness, I see that as the least silly part of NPS. Here I break down where I think NPS really fails, examining the recent "NPS of SAFe" article by Age of Product.The Age of Product web site recently published the results of their admitedly entirely unscientific SAFe NPS survey, and it’s been making the rounds on agile corners of social media.

There’s a good chance that many of you who have had the, eh… pleasure? of bumping into SAFe see that terrible score and feel some vindication. But you probably shouldn’t.

While you won’t hear me defending SAFe, I will defend statistical rigour today. And today I’m going to do that by examining Net Promoter Score (NPS).

Now let me first be clear: I’m not really poking fun at, or criticizing Age of Product for their post. In my view, they did a fun survey about a known controversial topic, mostly for laughs. There’s nothing wrong with that, as long as we don’t treat it as some ironclad conclusion. They even include the (later added) disclaimer on their post:

This is not an academic study that claims to be representative. It was a quick poll to understand how people feel about SAFe® and provide them with a platform to voice their opinion.

But this non-academic study does make for a great case study in why I believe NPS is so flawed. So let’s get started.

Problems with NPS

Data collection is biased

This is actually the core problem that the disclaimer at Age of Product alludes to. Those who participated were self-selecting, and of a particular demographic (presumably regular readers of Age of Product). Such people have inherent biases. We may be able to guess what they are–or not.

Most NPS surveys are also biased, alghough perhaps arguably less so. Most often a company asks all customers, or perhaps a random sample of customers, to rate their product or service after a transaction (purchase, custom service incident, etc). And they can’t force anyone to answer. So there’s a self-selection bias. Only those who want to answer for some reason (they love the product? they hate it? they’re bored?) will respond. But even if they could ensure that every customer responded, they’d still only get responses from customers. If you buy a widget from Acme Co, and you hate it, you’ll only ever answer the NPS survey once. But if you love it, you may buy hundreds of widgets, and have the chance to answer hundreds of times.

Statistical rigour of course isn’t the only thing to consider. And sometimes it’s not even necessary. After all, the goal of NPS isn’t (necissarily) to determine how “everyone” feels about a product. According the official web site, it’s designed to measure “customer experience” (a dubious assertion I’ll address next). So maybe a case can be made that repeat customers should be counted more heavily than one-time customers. It’s likely situational.

The core claim is dubious

“NPS measures customer experience”. Then why isn’t it called a “Customer Experience Score”? Well, a rose by any other name… How does NPS gauge customer experience?

NPS consists of one key question, which is answered on a scale of 0-10 (10 being best or most likely):

How likely is it that you would recommend [brand] to a friend or colleague?

So we’re claiming to measure “customer experience” but we’re not asking anything at all about customer experience. Seems a bit iffy to me. As if I asked you “Do you like MacDonald’s?” and took your answer as an indication of how you feel about drive-through restaurants.

Likely (in fact, almost certainly) there is a correlation between one’s experience with customer experience, and one’s willingness to recommend a product, just as there is a correlation between people who like MacDonald’s and those who like drive-through restaurants. But it’s nothing like a 1-to-1 correlation. Some will have a bad customer service experience, but still recommend the product; some will have a good customer service experience but not recommend the product. Some like drive-through restaurants, but dislike MacDonald’s; some like MacDonald’s but don’t like drive-through restaurants—or even own a car.

The question is utterly confusing

This is where the SAFe NPS score is really interesting. Think for a moment, then answer:

How likely is it that you would recommend SAFe to a friend or colleague?

Now I want you to think about what went through your mind as you were trying to come up with an answer.

Here are some questions I can imagine some might consider while debating whether or not to recommend SAFe to a friend or colleague:

- Have I been exposed to SAFe before?

- Did I enjoy using SAFe?

- Was it helpful in some situations, and maybe harmful in others?

- When do I ever talk about SAFe to friends and colleagues?

- Do I have any friends or colleagues in a position to ask for a recommendation?

- Wait… the only people who ever buy SAFe are VPs and CxOs. Do I know any of them?

- I am a CxO. That means the only colleagues who I might recommend SAFe to are the exact same people who made the decision with me to purchase it in the first place.

- I’m not a VP or CxO. The only ones I know are my boss(es). They don’t care about my recommendations.

I could go on, but I won’t. My point is: This is actively a silly question to be asking. When asked literally, the answer will almost always be 0 or “I would not recommend SAFe to a friend or colleague” even if, and this is key, you really really love SAFe. And the reason is simple: Most people don’t talk about SAFe to friends or colleagues in this way. Some do, sure. But most don’t.

Further, simply liking SAFe, and having friends or colleagues in a decision-making role where SAFe might be chosen isn’t enough to recommend it, if we’re truly honest. A good friend, even one who really really loves SAFe would only recommend SAFe (or anything else) if they thought it would help you. Maybe SAFe did wonders for them, but wouldn’t help you, and they think you should use something else. That’s perfectly valid. Does that mean you had a bad customer service experience (whatever that means, really) with SAFe? Obvoiusly not.

If you think this is only absurd because SAFe is a silly example, I challenge you to answer the NPS question in your own head for any brand or product. How about the device you’re reading this post on. How likely are you to recommend [the brand of your laptop, mobile phone, tablet, or PC] to a friend or colleague?

I imagine many of you are thinking something like “Well, I’d recommend this to my friend Jake, but not to my mother”. How do you put an answer like that into a 10-point scale?

And on the subject, what does “likely” mean anyway?

When I’ve discussed this casually with friends, I’ve asked people to disect the meaning of “likely”. And I get wildly different interpretations. Some will answer a 10 if they would recommend the service to one single person. (“Jake would love this!”) Others see the 10-point scale as more or less a probability. (“I would recommend this to Jake and Alice, but not my mother or Bob, so 50%… I’ll answer 5”)

Hypothesizing about the future is unreliable

Another aspect of the confusing question: It asks “how likely” are you to do something.

Humans are notoriously bad at predicting the future. Even when it comes to their own intentions.

This is the premise of the excellent book by Rob Fitzpatrick, The Mom Test. If you’re ever trying validate a business idea, I highly recommend reading it. But the premise is explained in the subtitle: How to talk to customers & learn if your business is a good idea when everyone is lying to you. In essence, the book teaches you how to ask questions so good that even your mom cannot lie to you.

“Mom, would you recommend my service to a friend or colleague?” “Yes, son, of course I would!” 🙄

Even when your mother isn’t the subject of your NPS survey, there’s very little reason to believe that someone answering 9 or 10 on a question about a hypothetical recommendation would actually make a recommendation.

The calculation is… weird

Let’s pretend that the question we’re asking is actually valid, though. So that we have some hope of getting useful insights from the responses. What does NPS then do with those responses?

It averages them, right? Eh, no. Not even close.

You calculate the percentage of 0-6 responses (“detractors”), and subtract that from the percentage of 9 & 10 scores (“promoters”), and that’s your NPS score. This can lead to some truly ridiculous outcomes. Suppose you survey 10 people, and they all answer 8. Your NPS score would be 0. Suppose half answer 9 and half answer 6. Your NPS score is also 0. Suppose 5 answer 6 and 5 answer 7. Your score is -50.

How is any of that possibly valid? I would assume that scores of 6-8 are “mostly good”. Not anywhere from “neutral to bad” as these scores seem to indicate.

Of course, what scores 6-8 really mean is confusing, as there are many ways to interpret the question as I already discussed above…

NPS’s superiority has been pretty thoroughly debunked

Not surprisingly, there have been accademic studies on the validity and accuracy of the NPS. And as Wikipedia points out, there is a lot of criticism. The common theme seems to be that, at minimum, NPS is no better than alternatives.

Yes, but…

Before I talk about alternatives to NPS, let me address the one objection that every NPS advocate brings up to arguments like mine:

Yes, but you can’t use just the NPS score! You must only use the NPS number as the beginning of your research."

If this is true, it raises serious questions about the usefulness of the score in the first place. If we admit at the outset that we can’t get meaningful insights from the score alone, then why even bother with that score?

Why not start by rolling a pair of dice, then “using that number” as a starting point to doing real, actual, relevant customer research?

So what about SAFe?

So getting back to SAFe… what can we know about SAFe from this survey?

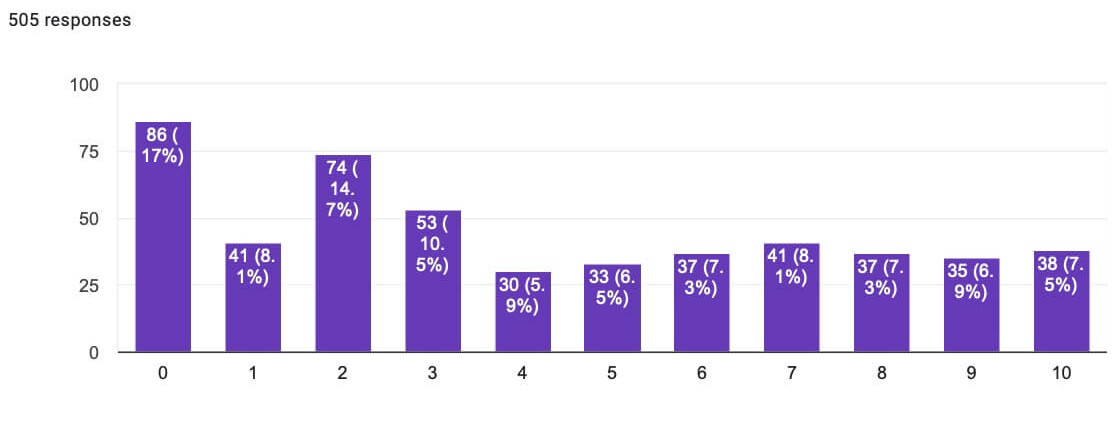

Well. Not much, really. All we know is that 56% more people answered 0-6 than answered 9 or 10 on a confusing question about recommending SAFe to friends and colleagues–a strange proposition on the outset.

Fortunately, Age of Product did provide more raw data, if you’re interested. It turns out that 86.9% of respondants had at least been exposed to SAFe once. (Rightfully, the 13.1% who hadn’t should be excluded, but at this point, who cares?) They also tweaked the question to be marginally more relevant to SAFe:

How likely would you suggest SAFe to a traditionally managed organization to achieve business agility?

At least this focuses the question a bit more than the stock NPS question.

And they also provide the breakdown of all answers, 0-10. And honestly, that curve is a lot more interesting to me than the NPS score:

Can this be improved?

No doubt. I’ll talk about some more general approaches in just a second.

But for the purpose of evaluating SAFe, I’d start by defining my goal. Am I interested in determining SAFe’s product market fit? If so, I’d probably ask executives and decision makers who have used SAFe about their experience. Am I interested in determining how individual contributors feel about SAFe? That’s an entirely different line of investigation.

Or maybe I’m interested in measuring the efficacy of SAFe in improving business outcomes. That, of course, is an entirely different matter.

Consider this: Even if -56 is the “true” NPS score for SAFe, it’s also concievably possible that one or more of these seemingly contradictory things is also true. This is to say: SAFe can be unpopular and also successful by any number of metrics:

- SAFe is commercially viable

- SAFe has achieved product/market fit by at least some metric

- Influential people are recommending SAFe to decision makers

- SAFe is effective at improving business outcomes*

So the first step toward a better survey is determining the actual topic we want to explore. With that in mind…

*To be clear: I’m not making any claim regarding SAFe’s effectiveness or ineffectiveness, only that it logically could be both effective and unpopular.

So what’s the alternative?

So if NPS is really so silly, what’s the alternative?

I’d love to give you a single, neat, tidy alternative to replace all your NPS.

But this is actually a big part of the problem: NPS tries to be a single, simple tool, for understanding a complicated, nuanced world of customers.

What this means is that if you actually care about real insights into your customers, you need to apply the right tool in the right situation. And since I don’t know your situation, I can’t possibly tell you the single best tool. (Also, I’m not a user research expert, so I don’t know all the best tools or how to use them.)

Product-Market Fit Survey

One alternative framework I like, which can replace many uses of the NPS, is the Product-Market Fit Survey.

This simple question aims to determine whether your product meets a need in the eyes of your target market. It’s superficially similar to NPS, in that it’s a single question wiht a multiple options, but it’s a much more pointed and powerful question:

How would you feel if you could no longer use [this product]?”

- Very disappointed

- Somewhat disappointed

- Not disappointed (it isn’t really that useful)

- N/A — I no longer use this product

Notice that there’s no ambigutity here. There’s no determining whether “My mom would like it, but Jake wouldn’t” counts as a recommendation. It doesn’t ask you to predict the future. It doesn’t conflate senses of probability. It’s very straight forward. Of course there is an element of subjectivity when it comes to how disappointed you might be, or what “very” means. But that’s kind of the point here… if your goal is to measure product/market fit, you want to find out how any of your customers are passionate about your product. Those people will easily identify as “very disappointed”.

Measure the actual thing

If your goal is to measure customer recommendations, instead of asking about future, hypothetical recommendations, what if you measured actual recommendations?

There are many ways companies we all know and love do this, from Amazon affiliate links to questionares asking “How did you hear about us?”

Are they perfect? Of course not. But they’re much more likely to deliver meaningful results than asking about an unbounded, hypothetical future.

What about measuring customer experience?

Ah, so you want to measure the thing NPS claims to measure in the first place? I’m no expert in this field, but I’m pretty sure that with a little bit of thought I can think of 5 questions that better gauge customer experience than “would you recommend?” For starters, how about:

How was your customer experience?

It’s still a bit vague. But at least we’re asking about the thing we care about!

Stay tuned

As I was writing this post, I had the idea to do a comparison of NPS versus the Product-Market Fit Survey for my regular readers. So I sent out a questionaire with the purpose of asking the NPS question and the PMF question. I threw in a few other questions for good measure, too.

I’ll be writing about the results of this survey soon. If you’re interested, be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss it!