Gervais, meet Westrum

The Gervais Principle, as dark as it may be, only explains a mere 80% of organizations.When I first read The Gervais Principle by Venkatesh Rao several years ago, it completely changed my life. I can’t think of any other book that has been so eye-opening for me.

It’s a 6-part blog post (or eBook) examining how organizational management works in most organizations, using the American version of The Office as its primary lens. Whether you’ve seen The Office or not, I encourage everyone to read at least the first part. If that hasn’t piqued your interest, the rest will bore you.

You’ve probably heard of the Peter Principle, the idea that people are promoted to their level of incompetence. Later came the Dilbert Principle, which says that companies promote incompetent people, to limit the damage they can do.

The Gervais Principle supersede both of these:

Sociopaths, in their own best interests, knowingly promote over-performing losers into middle-management, groom under-performing losers into sociopaths, and leave the average bare-minimum-effort losers to fend for themselves.

If you think that sounds dark, you aren’t alone. If you read the entire series, it only gets darker from there. And indeed the strongest criticism I’ve heard of The Gervais Principle has consistently been “it’s too pessimistic”. Of course that alone isn’t a very convincing criticism. What matters isn’t how “pessimistic” a theory is, what matters is how predictive it is.

In my experience, and apparently the experience of the author, The Gervais Principle does a pretty good job of explaining office realpolitik.

But I’ve always felt there’s something missing. I’ve always felt that while The Gervais Principle has pretty well explained my observed reality, there must be another reality that we can and ought to strive for, and hopefully even achieve, at least in some cases.

This is why when I learned about the Westrum organizational culture typlogy, it all started to make sense.

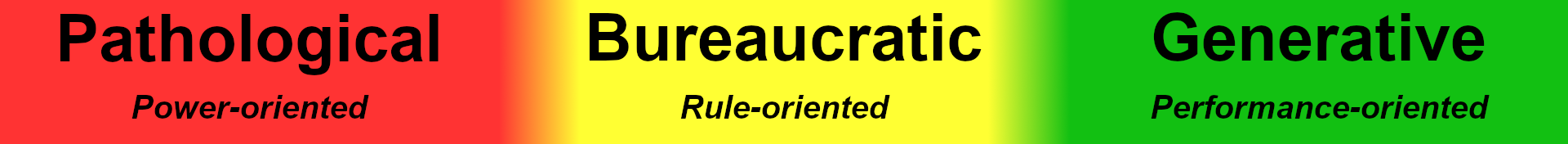

According to the westrum model, organizations exist along a spectrum, with three dominant typologies: Pathalogical or power-oriented, bureaucratic or rule-oriented, or generative or performance-oriented.

So here’s the thing: The Gervais Principle (and indeed the Peter and Dilbert principles, as well) describe organizations that operate predominantly at the Pathalogical end of the spectrum, and to a lesser extent in the Bureaucratic middle.

So what about the elusive Generative end?

Well, according to 2016 research done for the book Accelerate, only 21% of responding organizations self-classified as Generative. Matt K. Parker, author of A Radical Enterprise claims that only 8% of business globally operate in a “radically collaborative” fashion, which I would estimate describe a small subjsection of Generative businesses, the far-far right end of the spectrum.

So the problem, as I see it, is not that The Gervais Principle is too pessimistic. It’s that it’s not all-encompassing. It explains “only” a mere 80% of the organizations out there: The pathological and bureaucratic ones.